We talked to Associate Professor of Information Politics and Ethics Whitney Phillips about her research into political polarization and why it isn’t what it seems.

by Leo Heffron, Class of ’26

Few would argue that our political environment feels increasingly chaotic and polarized, and for many, this might seem like a fairly recent development. But Whitney Phillips, associate professor of information politics and ethics at the UO School of Journalism and Communication (SOJC), says our current political moment has 80-year-old origins.

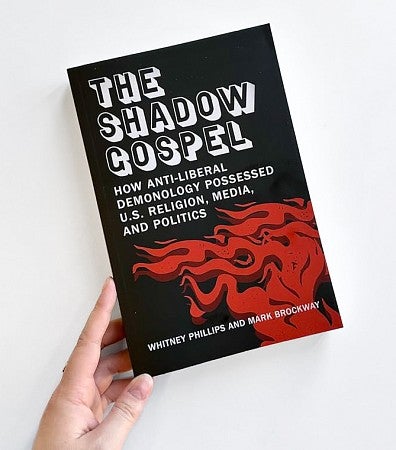

In her book, “The Shadow Gospel: How Anti-Liberal Demonology Possessed U.S. Religion, Media, and Politics,” Phillips breaks down how right-wing and evangelical media, starting around the time of the Cold War, helped shape an ever-changing villain out of “the left” and the Democratic Party — even demonizing conservatives. Over time, they built an anti-liberal narrative that painted liberals as a threat to conservative values, Christianity, families and America itself.

While the clash between “left” and “right” seems intuitive, it ultimately reinforces an overly simplistic story about the current political situation, Phillips says. Based on her research, she has identified three dynamics that complicate our understanding of political polarization:

1. The most potent source of religious messaging and influence in the United States is secular.

When people talk about religious influence in U.S. politics, they usually point to the rise of the New Right in the 1970s and ’80s. Groups like the Christian Coalition and Focus on the Family pushed a conservative, Republican and evangelical agenda. That era is often seen as the moment religion and Republican politics became deeply linked, with evangelicals supposedly voting based on a shared “love of God and Jesus,” Phillips said. But that’s only part of the story.

Over time, Phillips says, the actual influence of church-based religion within the conservative movement has shrunk — even as religiously charged language has gotten louder. Evangelicalism hasn’t grown much in terms of numbers, and the most prominent voices using religious rhetoric today are often not theological at all.

“You hear right-wing messages that sound religious,” Phillips said, “but they’re usually coming from cable news or from people with no meaningful connection to church.”

An example of this is Elon Musk, who identifies as a “cultural Christian” but says he doesn't necessarily believe in God or Jesus. In the 2024 election, he backed President Donald Trump of the Republican Party.

After Trump's victory, Musk used religious-tinged language to describe USAID as "evil," a term he has also used to describe the "woke mind virus" that he claims is setting the country on the path to apocalypse.

This kind of language might sound religious, Phillips argues, but it actually reflects the secularization of religious language. A lot of what gets passed off as “religious” in politics now isn’t really about faith — it’s more about using churchy language and symbols to rally people against perceived threats like immigration.

Sometimes, the contradiction becomes obvious. Christian organizations — like Lutheran ministries that help immigrants and the poor — have been targeted as too liberal. Despite living out traditional biblical values, they’re attacked by so-called “religious” political leaders simply because their work is seen as progressive, Phillips said.

That points to something deeper, Phillips said. Many politicians who present themselves as religious aren’t really trying to promote biblical values. Instead, they’re using religion as a tool to build power and push their political agendas, which is often just to fight “liberals,” even though “liberal” can often include conservative Republicans.

2. The most ruthless destroyers of Republicans are other Republicans.

The two main parties in the United States, Republicans and Democrats, are often pitted against each other. When we think of political polarization, our bipartisan, dominant political ecosystem seems to be at the center of the issue.

The idea that this polarization is based on Democrats versus Republicans lacks nuance, Phillips said. This is evident when we look at how the Republican Party treats its own members if they don’t agree with decisions made by the party leader.

This has been especially evident since the Jan. 6 attack at the U.S. Capitol. Non-MAGA Republicans have been targeted and pushed out of their own party — even when they hold traditional Republican values like states' rights, small government and free markets.

“An example of this is Liz Cheney, who these days is often celebrated by some people as being a liberal resistance hero,” Phillips said. “It wasn’t so long ago that people would criticize Liz Cheney because of her intensely conservative views.”

Many conservatives, like Cheney, have been ousted and are being aligned with liberals, even though they don’t share liberal values or policy goals. This destabilizes the usual polarization narrative, which assumes two oppositional sides, Phillips says.

3. Anti-liberal fear and loathing span the political spectrum.

The third myth is that disdain for liberalism is solely held by the right wing, Phillips said. This sentiment originated during the Cold War era, promoted by conservative and evangelical media, but it has evolved to span the entire political spectrum.

It’s not just the far right that’s skeptical of the media and government. People across the political spectrum are losing faith in institutions, which are generally associated with liberal ideologies.

“A growing percentage of self-identifying liberals and conservatives have suspicions about mainstream news, don’t engage with mainstream news, and instead they go to social media for information,” Phillips said. “The arguments that they give are often indistinguishable from each other despite having different political ideologies.”

If people across the political spectrum have doubts about the institutions that are generally associated with liberals, the usual framework for political polarization doesn't work, Phillips said.

Our current political environment seems chaotic and strange. If we want to understand and improve our political climate, Phillips argues, we need to let go of outdated guidelines and look more honestly at how people are behaving and communicating, not just at how we assume they’re supposed to.

Leo Heffron is a third-year journalism major at the SOJC, with a minor in Spanish. He loves to write about many topics, but fashion and social issues are among his favorites. You can find his work in The Daily Emerald.