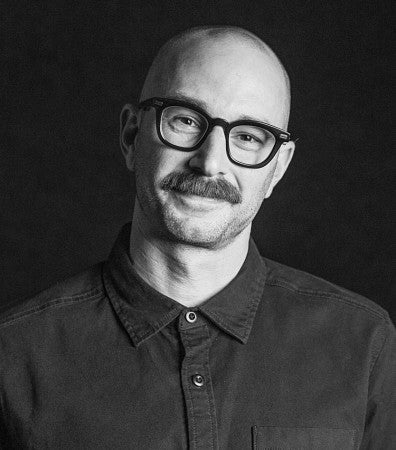

John Sutter

Assistant Professor of Science Communication

Hometown: Oklahoma City

Primary research interest: Finding new and more effective ways to tell the story of the climate crisis that will resonate with people while fostering environmental communication programs

Hobbies: Trail running, canoeing, backcountry skiing

Favorite author: Walt Whitman

Favorite artist: Filmmaker Patricio Guzmán, especially “Nostalgia for the Light”

Favorite quote: “The eyes of the future are looking back at us, and they are praying for us to see beyond our own time.” —Terry Tempest Williams

Say “hello!”: Follow him on X or Instagram, or connect on LinkedIn.

John Sutter believes that if you want to understand the world, you have to go out and “muck around in it.” For Sutter, a new assistant professor of environmental communication at the School of Journalism and Communication (SOJC), that means getting outside to ski, run and enjoy the rivers and lakes. As a faculty member, his role is to teach students how to bridge the gap between scientific understanding and effective storytelling. But to do that successfully, they need to explore their local environment and experiment with new media platforms, he said. And they need to find their voice.

Sutter’s work, which includes reporting for CNN and environmental documentaries “Baseline” and “Planet A,” emphasizes the importance of clearly articulating the science behind climate issues. With this focus he aims to not only highlight the scientific basis for those issues, but also emphasize the current and future humanitarian repercussions.

Sutter, who will join the SOJC faculty this fall, has a varied background in teaching, journalism and multimedia storytelling. Before accepting the UO position, Sutter worked as the Ted Turner visiting professor of environmental media at George Washington University in Washington, D.C. In 2005, he graduated from Emory University in Georgia with a bachelor's degree in international studies and journalism. In 2023 he earned his master's in film and media arts from the University of Utah in Salt Lake City.

Sutter’s interest in environmental media and storytelling is deeply rooted in his commitment to climate and environmental issues. He intends to encourage students to explore their local environment and experiment with new media platforms.

Sutter, in his own words, went further into his career and projects.

Who has been the biggest influence on your career?

John Sutter: Jan Winburn. She was my editor at CNN for about a decade, and I learned most of what I know about narrative storytelling and how stories function from her. She helped me find my voice as a writer and storyteller — like my individual storytelling voice, not just an institution’s voice. That was so important for me. Finding your voice matters way outside of the workplace, of course. I see that as one of my main roles as a teacher — helping students express themselves in nonfiction.

Why did you decide to join the SOJC faculty?

JS: There were multiple specific reasons related to the quality of the faculty and the focus on science and environmental communication, especially with the Center for Science Communication Research. But the deciding factor was that it just felt right to me in my gut. There was an intangible feeling I got when I visited the University of Oregon that made me believe I’d be able to thrive here — that it was a creative and inspiring place where I could contribute something meaningful. I want to be part of a community of people who really care about students and want to make a difference, and I found that in the faculty I met when I visited campus for interviews last year. I’d first visited Eugene years ago as a reporter covering a court case, and I was struck even then by the specialness of the place. It's this little place with big ambitions and big ideas. I really want to be part of that.

What do you hope to accomplish here?

JS: I want to help students create publishable, professional work. I also want to help grow or deepen the university’s commitment to environmental storytelling and communication.

What do you hope students will gain from your environmental communication classes?

JS: I want them to find their own voices as storytellers, and I want them to engage more deeply with the world around us. I think to really love the world, you have to pay attention to it. You have to get out there and muck around in it a bit. So I want them to feel a sense of agency to get out and explore. And I want to give them tools to help make that exploration fruitful and relatable for audiences.

Much of your past work has been tied to the environment or climate crisis. What caused you to develop a strong interest in that topic?

JS: My grandparents were in the Dust Bowl. Farmers over-plowed the Great Plains and sent walls of dust racing across the land, blackening the sky. Something like 350,000 people fled west toward California, including one of my grandparents. I heard those stories growing up and had the profound sense that we can screw up the natural world if we don’t understand and respect the Earth systems that sustain and connect us.

Cut to me working as a newspaper reporter in Oklahoma right after college. The climate crisis was getting some early attention because of a big UN report. I started to realize this issue is going to reshape not just one region but the entirety of the planet. And the industries that drove Oklahoma’s economy were the main culprits.

I got totally fascinated by it — by its complexity, by the fact that lots of storytellers avoid it because they see it as too confusing or because it’s (needlessly) seen as overly political or controversial. I got interested in the hugeness of the issue both in timescale and geography. Carbon pollution stays in the atmosphere for something like 1,000 years. It’s just unlike any issue, and I think we have a moral responsibility to do more.

Your portfolio identifies you as a journalist, filmmaker and visiting professor. What would you classify as your main interest?

JS: I’m someone who’s interested in stories and tends to follow those stories into whatever medium seems to make the most sense at the time. I like working across mediums because it feels more creative and because I kind of like the challenge of it (even if it can be a little maddening). Right now, most of my work is in documentary filmmaking. That and teaching. But I worked as a journalist for many years, including at CNN, and I can’t not think of myself as a journalist.

What drew you to the topics of the two documentaries and what do you hope to accomplish with them?

JS: “Baseline” is about three kids growing up in the climate era — and it follows them from now until the year 2050. I’m the director of that project, which is supported by the International Documentary Association, Harvard, MIT, National Geographic and others. The young people I’m working with are in Alaska, Utah and Dominica. The film aims to counteract “shifting baseline syndrome” — the idea that environmental change happens slowly enough that we aren’t able to observe its true magnitude. By following these stories over time, I’m hoping to stretch our collective memory and turn a different kind of lens on the climate story.

I’m also producing a film called “Planet A,” which follows a research team on its final trip to the ice shelf at Antarctica’s “doomsday glacier.” Emelie Mahdavian is the director, and it’s supported by the Sundance Institute, Sandbox Films, Howard Hughes Medical Institute and the Catapult Film Fund, among others. This is a rare and cool group of researchers for a bunch of reasons — one reason being that it’s a team of six women and one man. The film aims to show the diversity that does exist in the polar sciences even if that’s rarely seen in the media. (The typical glacier film has a very bro-adventure energy that we’re not going for here). The story is also super important, as Thwaites Glacier, the so-called doomsday glacier, holds back several feet of sea level rise. It matters greatly in terms of what the Earth’s coasts look like in the future. These scientists are facing something enormous and scary and yet they choose to persist; they don’t give up, which I find inspiring. And I think their model for collaboration and perseverance is something we all could adopt.

You’ve had experience reporting on the climate crisis for multiple news organizations. How will this shape the focus of your approach in classes?

I’m a wide-lens kind of guy. I expect to be teaching a range of courses dealing with environmental issues and how they’re handled — or could be handled — by the media. I feel comfortable teaching students to work in a range of mediums, from documentary to narrative writing and podcasts. I’m sure some classes will focus on a particular medium or topic area, but, for some courses at least, I hope to give students the flexibility to explore the mediums they find most compelling.

I taught a class at George Washington University last semester, for example, where students published their own newsletters on Substack and submitted TikTok stories as assignments. One potentially annoying but, I think, exciting thing about the media landscape is that it’s constantly changing and evolving. There’s lots of fertile ground for creativity and collaboration and new approaches.

What are three things you want every student to know about you?

I love what I do. I can help you create publishable work. And I’m a tough but fair grader :)

—By Ethan Donahue, class of ’26

Ethan Donahue is a journalism major with a double major in history. He is part of the School of Journalism and Communication’s direct-admit and honors programs. He is also part of the Clark Honors College. He holds an interest in investigative and conflict journalism and is working on a thesis focusing on how journalism, propaganda and the U.S. government interact during conflicts.