Have you ever wondered what it’s like to be wrongfully detained in a foreign country—or how to advocate for those who are? Award-winning journalist Jason Rezaian will be on campus on Wednesday, January 24, for an in-person conversation and Q&A about the 544 days he was imprisoned in Iran, advocacy for hostages around the globe, journalists exiled from hostile regions and the use of visual forensics in search of the truth.

Rezaian, who is global opinions columnist for The Washington Post, will deliver the UO School of Journalism and Communication’s 2024 Robert and Mabel Ruhl Lecture at 5:30 p.m. on Jan. 24 in the EMU Ballroom on the Eugene UO campus. The SOJC hosts the most influential voices in mass communication for this annual event. Learn more about the event and register.

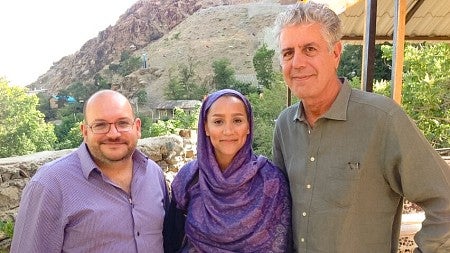

In July 2014, while serving as The Washington Post’s Tehran bureau chief in Iran, Rezaian and his wife were abducted by Iranian authorities and accused of espionage. He spent 544 days in Iran’s most notorious prison for political prisoners, Evin prison, as a wrongfully detained journalist. Since his release, Rezaian has dedicated his life to advocating for freedom of speech, freedom of the press and rights for journalists abroad and at home.

Rezaian hosts the acclaimed Spotify Original podcast series “544 Days,” based on his 2019 best-selling memoir, “Prisoner.” The podcast details his time as a hostage in Iran, including periods of solitary confinement, and reveals the extraordinary efforts made to secure his freedom.

We sat down with Rezaian ahead of his talk to find out more about his background and what he will speak about on January 24.

SOJC: To students who are interested in your reporting, how would you describe what it's like to be a global journalist working for The Washington Post?

Jason Rezaian: When you say it like that, I have to remind myself that this isn't a dream, that I have the incredible good fortune to write for not only one of the leading newspapers of the world, but a really important institution in our country and our democracy. So it's a privilege. It's an honor. It also feels like a great responsibility to get things right.

If you had told me 12 years ago that the Post would hire me and that I'd be here for more than a decade, and then all of the things that happened to me would have taken place, I could not have imagined a lot of it. But I do feel very fortunate and very excited. I'm talking to you right now from The Washington Post offices, looking around the walls that have old headlines going back more than 100 years and seeing colleagues, some of whom you see on television or read online. And I’ve got to pinch myself.

SOJC: With all your reporting and journalistic work, from the San Francisco Chronicle to the Times magazine to The National, what were you trying to accomplish?

JR: Through all of these projects, there was one consistent throughline: I was trying to explain the experience of a country and a society on the other side of the world that we have had a limited understanding of here in the United States for decades. And just try and make it a little bit closer, a little bit more accessible and a little bit easier for American audiences to understand.

SOJC: What was it like being imprisoned in Iran's most notorious prison for political prisoners?

JR: It is so hard to encapsulate that into a few sentences. And I will say, a year and a half is a long time. And I had a lot of different experiences, ups and downs — mostly downs. But as a reporting exercise, I can't imagine ever being thrust into a situation with more opportunities to be observant and try and chronicle. And imagine, I didn't have a pen and paper or journal to keep in prison. Those experiences are seared into my memory. I could just tell you blow by blow what those 544 days were like.

What I've tried to do instead is offer some context and some lessons that we can learn from the experience that I and others have had in that prison. And I think it has been a bit of a silver lining, right? Through the most traumatic experience imaginable, I hope that I've been able to extract something from it that will be of meaning to other people.

SOJC: You mentioned that out of all the projects you’ve been associated with professionally, your podcast “544 Days” is the one you’re most proud of. Why is that?

JR: We did a really good job of telling a story. On the first day that we met, the editor and producer asked me, "What do I want this to be?" I said, "I want this to be a blueprint for someone if their loved one gets arrested and taken hostage on the other side of the world."

One, it is a guidepost for people who are advocating for loved ones that are locked up abroad. Two, it’s a piece of content that hopefully is informative and entertaining. And three, and most importantly, raising awareness for issues that traditionally, we haven't had a lot of attention placed on. And if I'm being honest about it, each one of those things has a bit of an ulterior motive. I feel much better about myself and what I'm doing if the stories that I'm telling are shining a light on other people that are being held hostage on the other side of the world and driving a resolution to bring them home. And it helps me sleep easier at night if I'm being helpful.

SOJC: Why is it important to advocate for and protect freedom of speech, press freedom and journalists' rights around the world?

JR: We are at risk of losing our freedom of expression way more than we acknowledge. There have been so many more encroachments on our ability to express ourselves around the world and here at home in the U.S. over the last several years. That's only going to get worse. So it's super important that people who have experienced having their expression stripped from them in countries run by authoritarian leaders like Iran stand up and say, "Hey, this is what we risk losing.” And if my experience is an example of that that can be emblematic of a cause, I'm happy to use it for that.

But sometimes it's very hard for people who haven't been put in that situation to fully wrap their heads around what that would be like. Just imagine that one day, I was a guy living his life and had an iPhone that I was using. And then it was taken from me along with everything else. For the next year and a half, I didn't send a tweet, a text message or an email. I couldn't check the news. I couldn't communicate with anyone. I couldn't tell a story of what was being done to me.

And at that time, the world was talking about me. The Washington Post and the international media were telling the story of me being imprisoned in Iran unjustly. And the Iranian authorities were telling the story of why they were justifying my imprisonment. The piece that was missing was my perspective.

And as someone who's had that ability stripped from them and now regained it, I can tell you, it is one of the most vital parts of 21st-century life in an open society to be able to stand up and say, "This is me. This is my experience." And to have it taken from you is obviously not something that anyone should have to endure, and it's not something that anyone can just accept. When it happens to you, you understand what you've lost. I hope that I'm able to transmit some of that experience to people so that they really put more stock and effort into maintaining what they have.

SOJC: What assumptions made by Americans do you try to disrupt?

JR: One, this idea that Iranians are against connection with the outside world, especially the United States. And two, that women are content with being second-class citizens. The assumption when you see a country that has laws like that dictating how women dress and what they can and can't do is that somehow women have accepted a lesser role in the society. Nothing could be further from the truth. Since the 1979 revolution in Iran, women have pushed for more opportunities and rights within what is really a rigid and unfair system and have carved out opportunities for themselves to the extent that Iranian women are more educated on average than their male counterparts.

SOJC: What insights and perspectives do you hope attendees will gain at the lecture?

JR: I would love for people to walk away from the lecture and the conversations that follow it with a better understanding of what goes into major news organizations’ products today and how this industry works right now.

Two, I want people to understand the risks of going into journalism, especially on the international level. Importantly, as an opinions columnist, I want people to understand how the work that they do can potentially affect policy, which is something that I've worked a great deal on in recent years when it comes to press freedom issues and hostage issues. I've taken a very bitter and traumatic lived experience and tried to translate it into storytelling designed to make a difference. And if people walk away with a sense that they're better able to do that than when they walked into the room, I would feel very good.

SOJC: How do you hope the Ruhl Lecture and conversations at UO will further your advocacy efforts and provide younger generations with a fresh perspective?

JR: I love getting out and talking to groups at universities, because you're the next bearers of this baton. And to get out into different parts of the country and talk about these issues is a real opportunity to start conversations that I hope will continue in your dorms and your classrooms and when you're out and about with your friends, but also when you're consuming news and information and learning about other parts of the world — to realize that we still have an incredible set of rights, privileges and opportunities that people in most places around the world don't have. But those privileges are not God-given. They're not a birthright. We have to maintain them, protect them and grow them. Otherwise, they'll wither away. And so having these kinds of opportunities to connect with the younger generation as you prepare to step into your careers is really important to me and a real gift. And hopefully, it can be an opportunity for all of us to grow together.

SOJC: What’s the best piece of advice you could give to students, especially to those hoping to enter this line of work?

JR: Make yourself indispensable for whatever role that it is you want to have. If you want to be a journalist covering a specific beat, or if you want to be a communications professional in an industry, know a corner of that space or that industry better than anyone else.

Two, invest in becoming the best writer you can be. Because no matter what sort of job you have, communicating your ideas in the written word is something that will pay dividends throughout your life. No matter what it is that you do, you will never regret being able to communicate your ideas more clearly, more succinctly, and just really being able to connect with people. And our verbal and written communication skills are really all that we have when we strip everything else away. I know a lot of people say, "Well, I'm just not a good writer." You're not a good writer because you haven't spent the time to become one. Anybody can do this, right?

—By Sydney Seymour, class of ’25

Sydney Seymour '25 (she/her/hers) is a media studies major minoring in ethics. She is a writing intern for the SOJC and the executive writing editor for Align Magazine. Connect with her on LinkedIn.